In January 2020, Albert Willner, his hiking and army buddy Mike Bayles and I travelled to Poland for his endeavor to walk the Death March his father survived in January 1945.

In preparation for a presentation to the Adventurer's Club of Los Angeles, I wrote down my recollections of this expedition and Albert edited and contributed to the story.

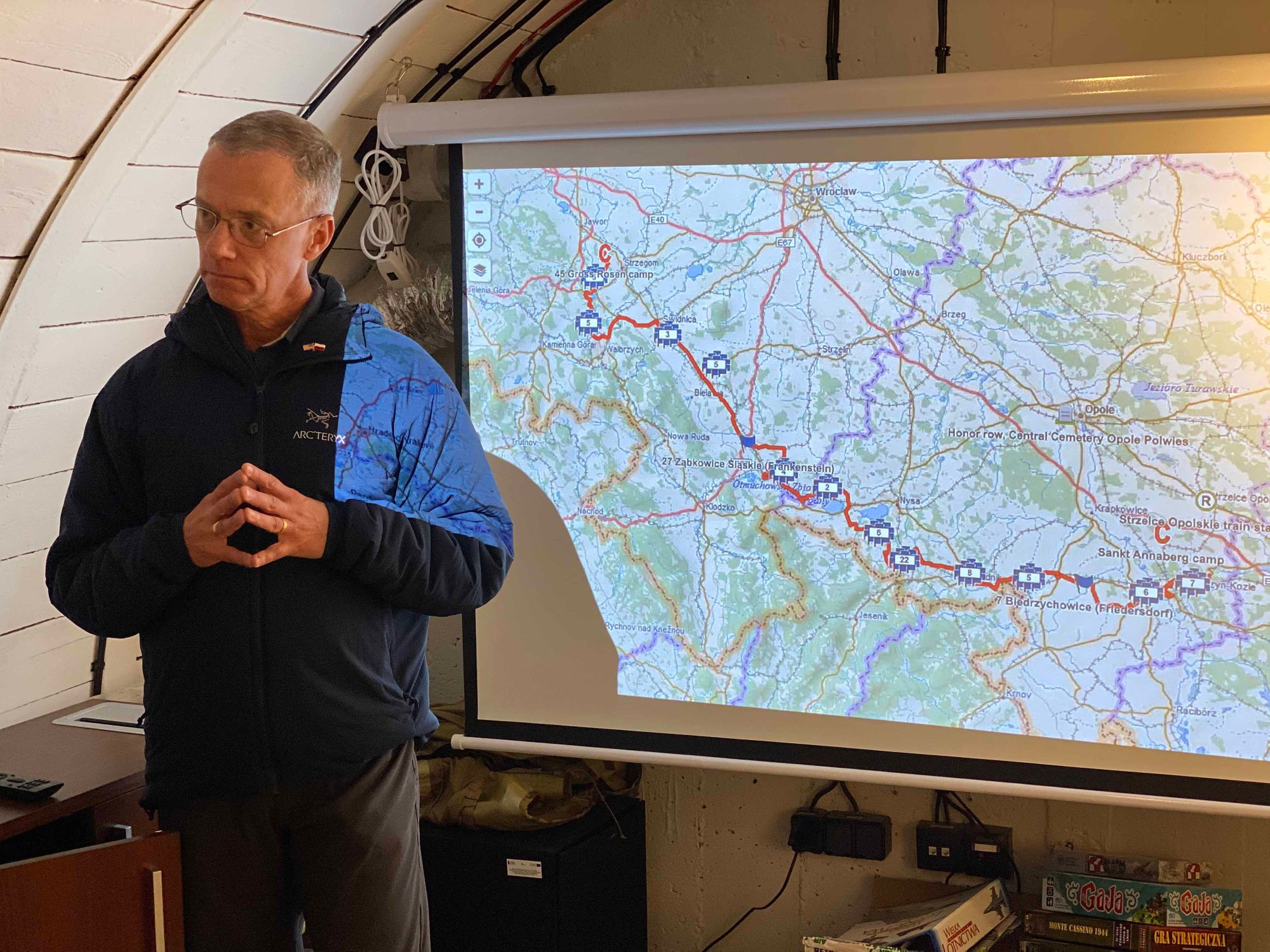

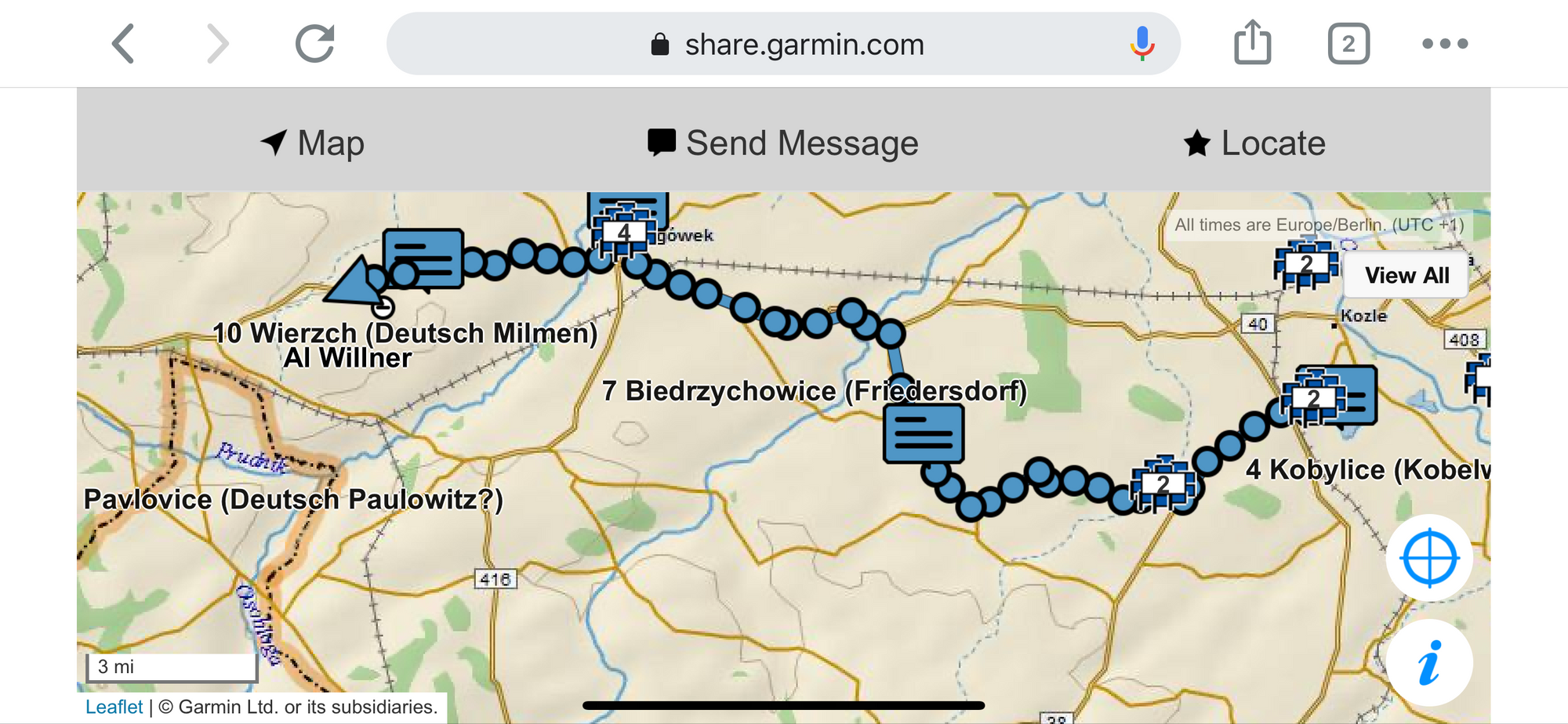

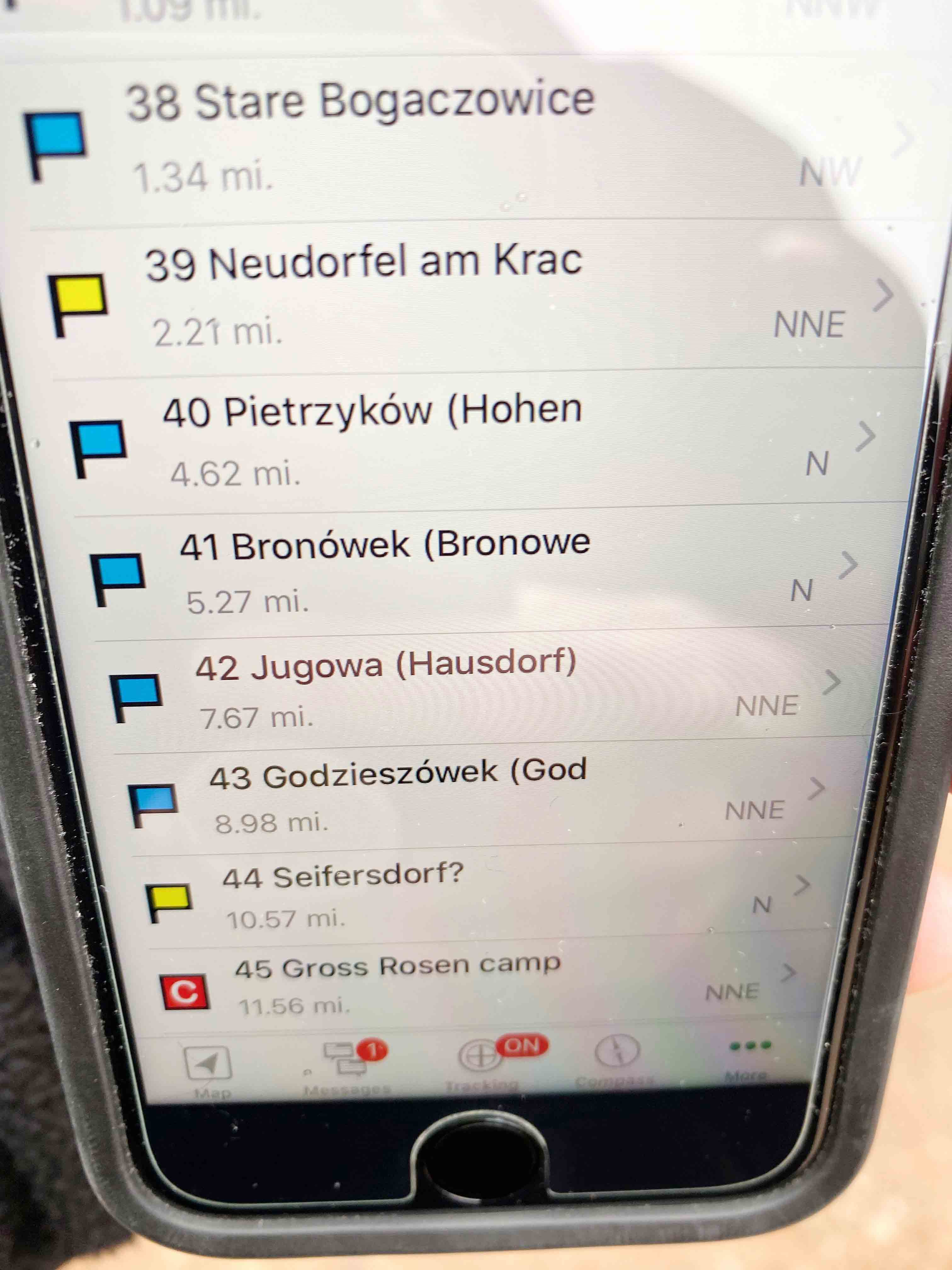

The second part of our journey which Al would be undertaking on the 75th anniversary of the Auschwitz-Blechhammer-Gross Rosen Death March was the Walk in Remembrance. He and fellow U.S. Army retiree Mike Bayles would set-out at 9am on the morning of 20 January 2020.

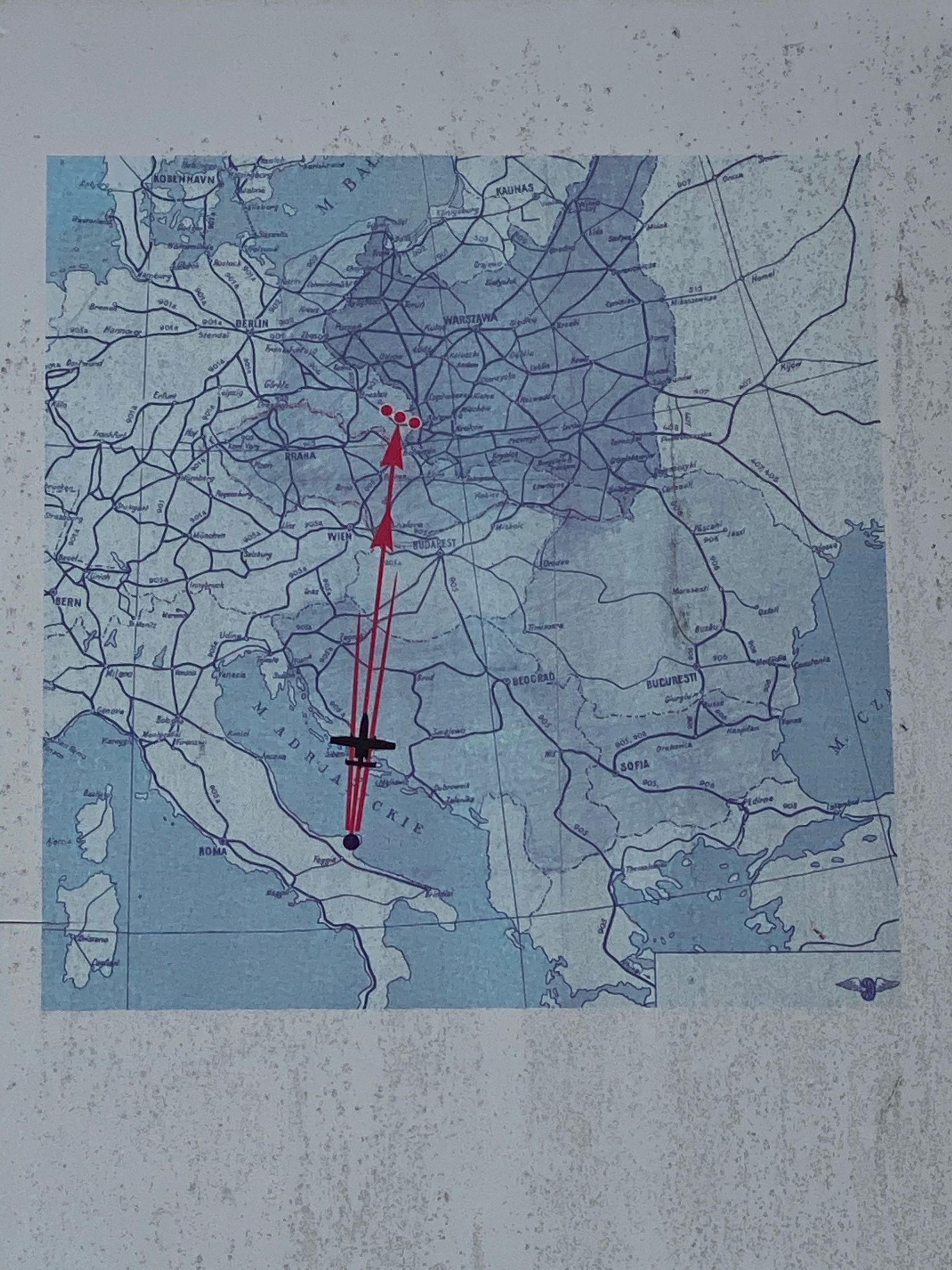

The death marches and transportation of concentration camp inmates to Germany during the winter of 1945 was one of the most horrific and tragic events of the war as the Germans forced prisoners back to Germany as slave labor. Thousands froze to death and were executed along the routes, leaving a trail of bodies that were often left for days before civilian work parties were organized to bury the dead in mass graves in adjacent fields or outside cemetery walls.

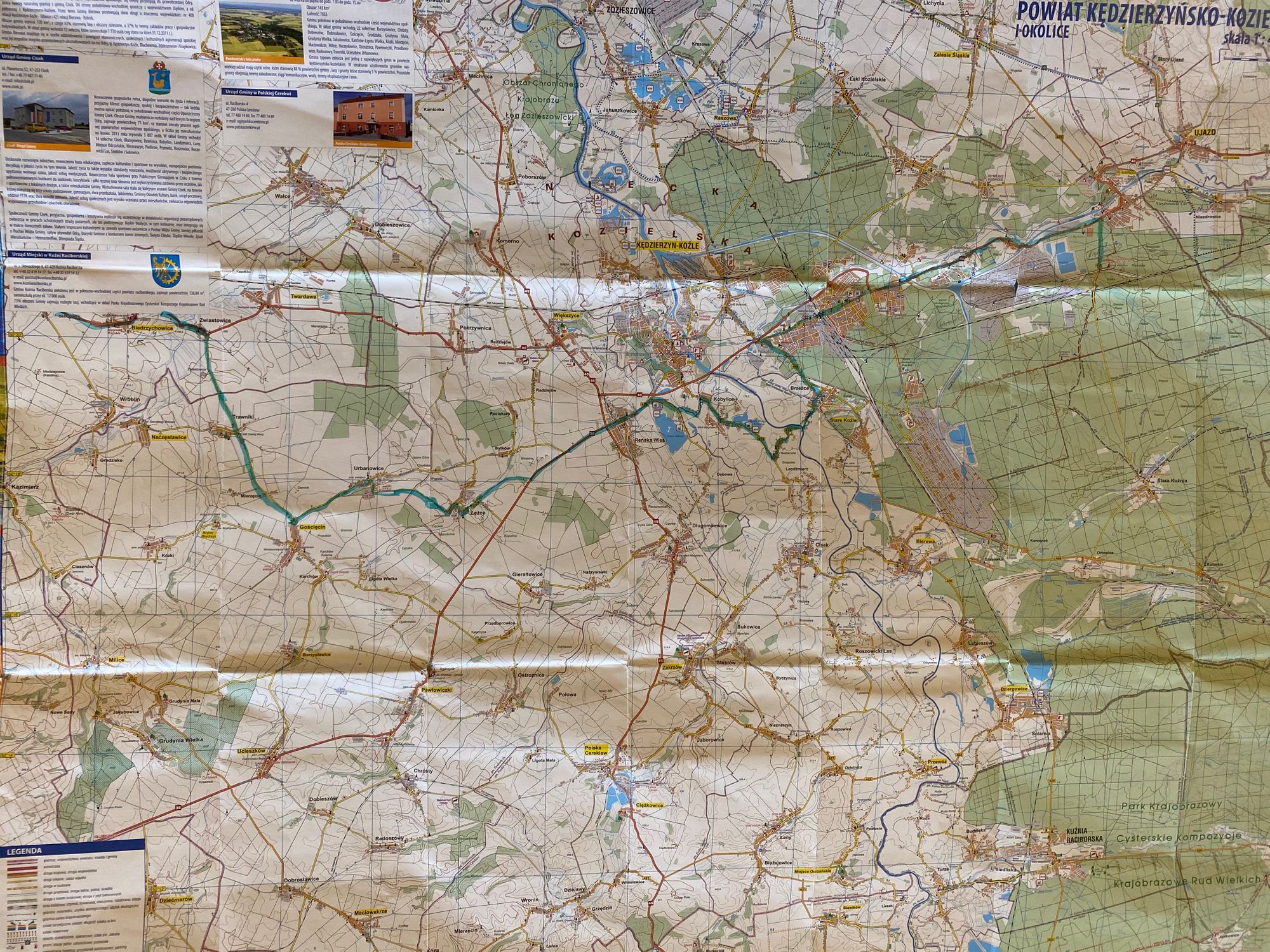

My role would be primarily to document the walk and to post daily blog entries on The Documentarian website. I would help coordinate provisions, updates routes, possible non-camping lodgings, media and local liaison and scout out potential camping locations. The route was already pretty well established though as more information surfaced from local historians there were slight changes to Walk in Remembrance.

This was the first time (that we know of and also according to locals) that anyone had actually walked the complete route of the Auschwitz-Blechhammer-Gross Rosen Death March. There was Polish press interest in covering the walk. We had reached out to the NY Times and Washington Post, but their coverage interests were focused on the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz (24 January 1945) which happened a few days after Eddie Willner and 4,000 other inmates had left Blechhammer and Auschwitz.

Al and Mike had planned to do the walk in 10 days, averaging between 15 and 20 miles a day. The weather, though cold and at times rainy and snowy, was quite moderate compared to 1945 which was one of the coldest winters on record.

The route presented many challenges. Most of march was on smaller country roads or along dirt roads through fields. The Nazis SS guards leading the march wanted to avoid main roads because of the chaos and congestion created by fleeing refugees and military convoys, but also to keep away from towns in order hide their actions from the German civilian population.

Traffic, even on the smaller country roads was nerve-racking. Al and Mike always walked facing oncoming vehicles, ever vigilant for speeding trucks and erratic driving. Language was an obstacle as none of us spoke Polish. (We did have a letter of introduction in Polish about what we were doing from our Blechhammer Museum friends) Al's German helped somewhat as there are remnants of the former German residents of Silesia.

Finding a protected camping place next to a water source was difficult. On our summer drive surveying the route, we passed many WWII-era abandoned barns. Since Al's father had recounted that each night the SS would procure barns or camped in fields to house the thousands of prisoners, the idea to find shelter in them was in keeping with what his father had experienced. However, what looked like deteriorating and abandoned barns, were actually well supervised property.

Though the route of the death march was generally through rural terrain, there were always people watching and vigilant of suspicious and unusual activity like foreigners hiking in the dead of winter. In one situation, a resident followed them out of town and called the police who stopped them on the small country road. After presenting the authorities with an explanation (the letter of introduction) of what they were doing they were allowed to proceed. Later in the day when it was time to look for a camping spot they happened across the same police patrol who guided them to an abandoned Jewish cemetery where they could camp. They were not keen to sleep near a cemetery, but night was upon them and the police expected them to stay there, so they had little choice but to find a spot outside the cemetery grounds in the woods.

The weather in Silesia in winter is changeable. During the day it rose to above freezing and was mostly sunny. However, they were hit with drizzling rain, high winds, early morning frozen fields and slippery frost and overnight snowfalls. Out of the 10 nights spent on the walk, they found camping sites for five nights and the other five nights were spent in sheltered places such as a school, a recreation hall, a park storage facility and even after much refusal (because Al did not want sleep in a bed), a guest cottage (all hosted by people interested in our trek and wanting to help) (I also overnighted with them in the studio cottage hosted by Poles of German origin.)

I had rented a car and as Al and Mike walked the route, I would meet up with them and spend some time to photograph and record part of their day. Al was mapping their route using Garmin GPS which I could access on my phone to see where they were. I tried to time my meetings with them to photograph them at different locations of interest – small villages, open fields, mountain forests, lake side campsite and historic cities. They were also taking pictures and recording their progress. I based myself for two to three nights in towns, hopscotching my way along the route.

As the walk progressed more people learned about Al and Mike's walk. In Prudnik, about half way through the walk, a VIP reception committee including the Mayor greeted them outside City Hall. Al and Mike had been delayed by a lengthy Norwegian television interview, so they arrived after sunset. Nonetheless, the organized tour of the city which highlighted its Jewish history as well as the tragic massacre of Hungarian Jewish women from the textile factory, was carried out well into the freezing night. We ended up at the synagogue (no longer in use) where a monument to the victims has been erected. In keeping with Jewish tradition, Al, as at other massacre memorial sites they passed, placed a stone on the memorial in memory of their souls.

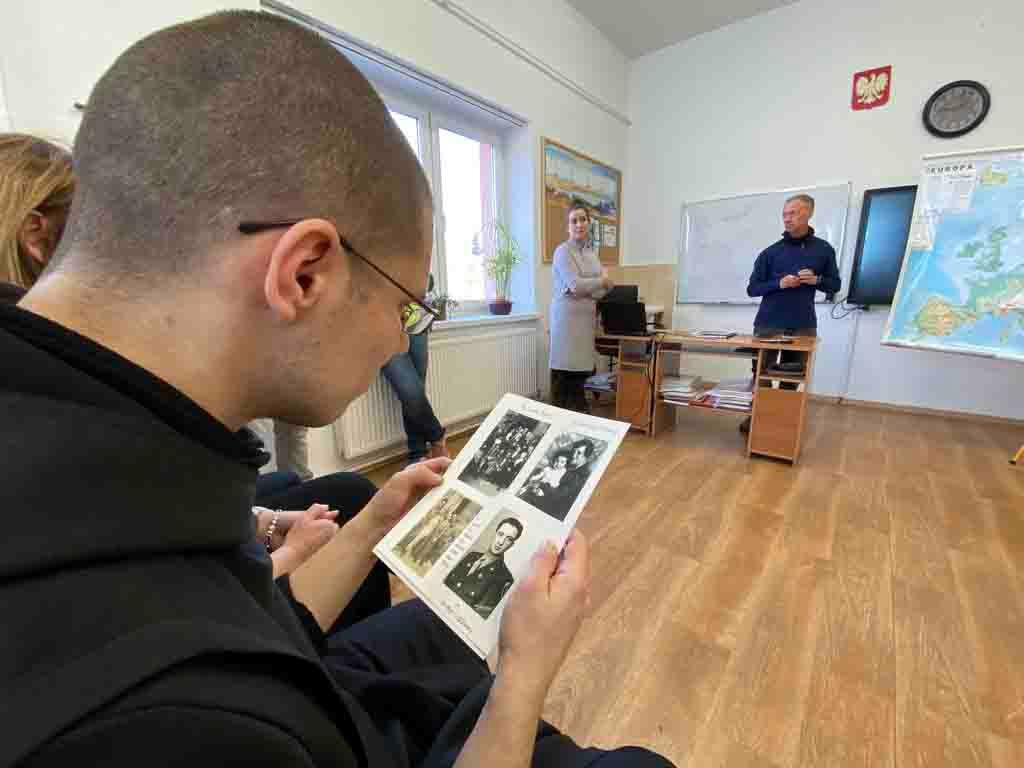

As part of his Walk in Remembrance, Al had hoped to share his family's story as well as acknowledge the terrible suffering of the Polish people. Al gave a couple of lectures to school children and citizens. Local newspapers and radio press covered portions of his walk. He was asked to attend a memorable service at a massacre site which school students did annually.

On the last day of the walk, a marathon 30-mile effort from snow-covered mountains to wind swept open fields and through a granite mine, they were met (well after sunset) at the Gross Rosen Concentration camp by the museum director and his staff. Accommodations had been arranged for them in the museum annex and office area which once had been the SS administrative building outside the camp. Again, not what Al or Mike had wanted, but they had no other choice but to recognize the courtesies by the museum staff anxious to support the venture. The next morning when I joined up with them, Al remarked he had felt a strange presence during the night. On a private tour of the camp by a local historian, she recounted how (in certain locations) she has encountered unexplained apparitions and sounds.

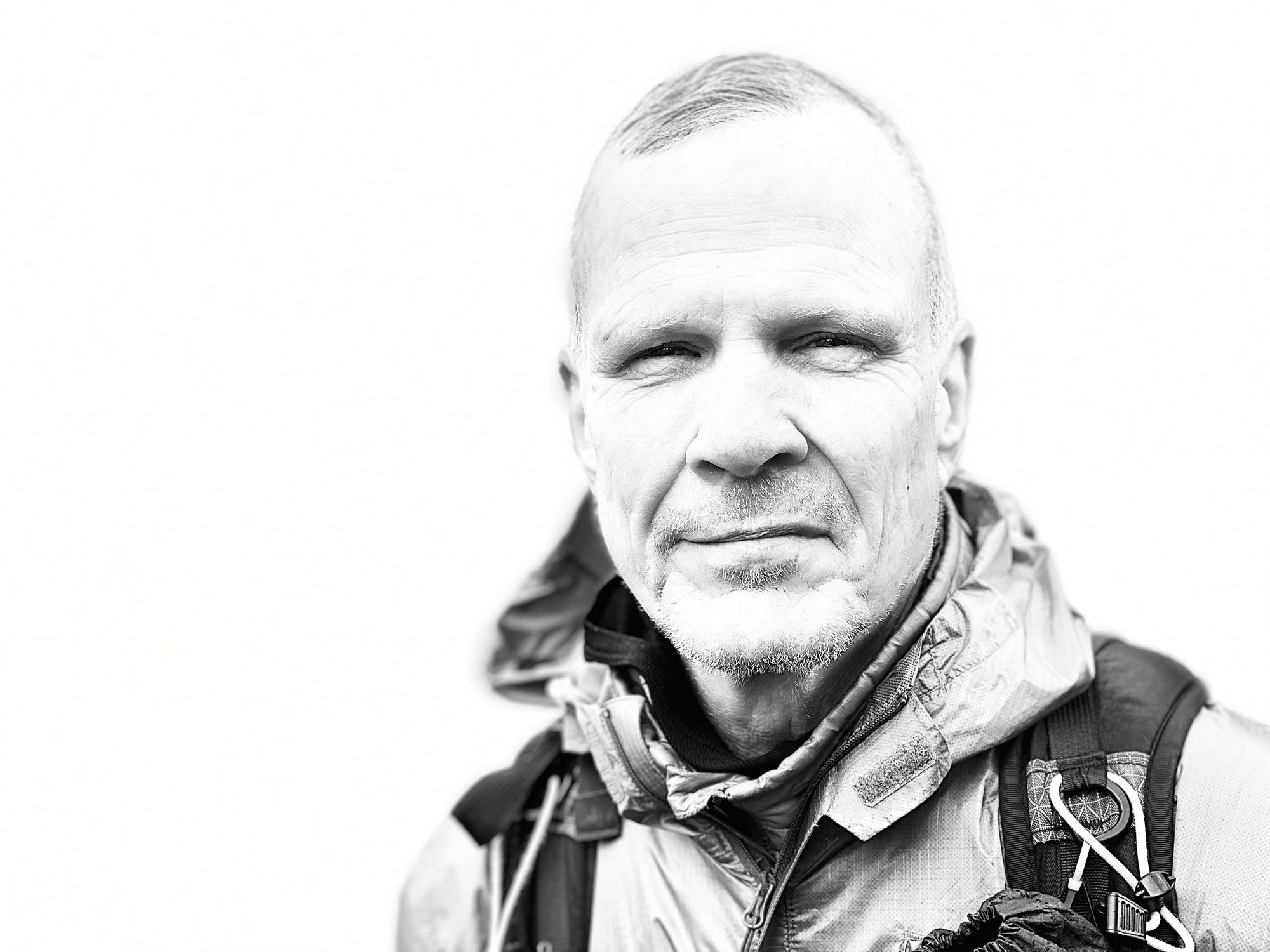

Upon his arrival at the Gross Rosen Concentration camp, Al took a moment of reflection alone on the Appellplatz where 75 years early his father had stood much of the night as Death March survivors continued to perish by collapsing and freezing to death or drowning in knee deep mud.

A reconstructed gallows and guard tower looms over the hallowed parade ground.